Against All Odds: The Path to the First Flight

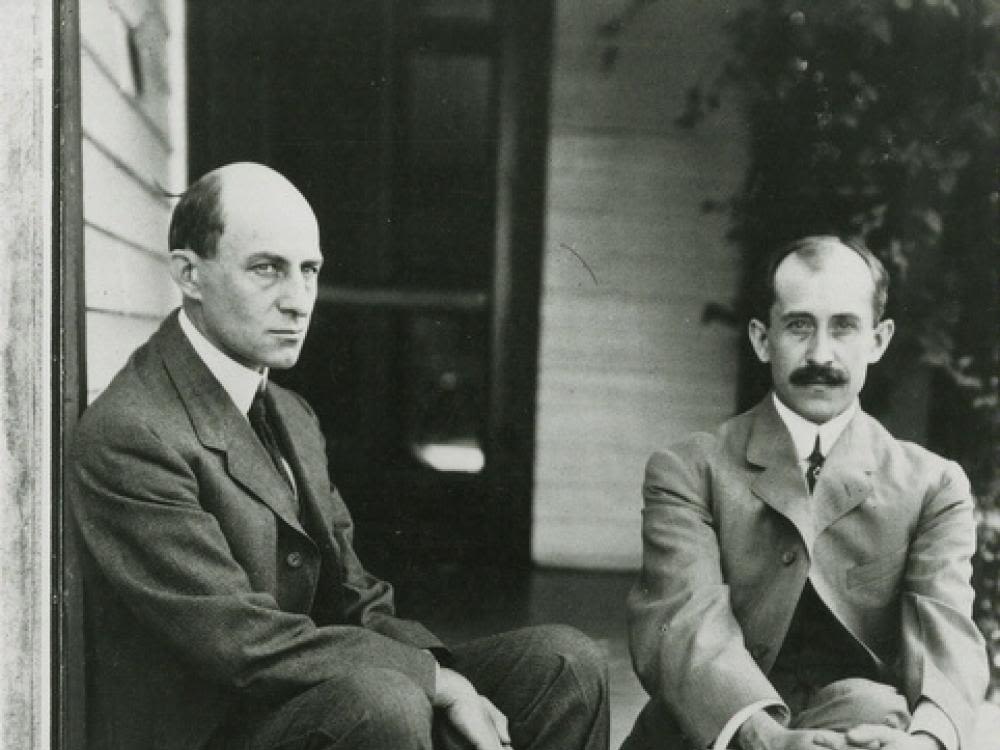

Before 1903, the idea of human flight was relegated to the realm of dreams and science fiction. Then came Wilbur and Orville Wright, two bicycle mechanics from Dayton, Ohio, who dared to turn fantasy into fact. On a cold December day, they piloted the Wright Flyer, the first successful heavier-than-air powered aircraft, into the history books. Their triumph wasn't a sudden miracle, but the culmination of years of relentless curiosity, tireless experimentation, and unwavering determination. But where did this burning passion for flight originate? What challenges did they overcome? Join us as we explore the inspiring journey that led to the first flight and forever changed the course of history.

Discover the thrilling story of aviation history in our blog post 'Pioneers of the Skies: The First Non-Stop Transatlantic Flight'.

Spark

The spark of Wright's lifelong fascination with flight can be traced back to 1878, when their father, Bishop Milton Wright, brought home a rubber band-powered toy helicopter designed by French aeronautical pioneer Alphonse Pénaud. The brothers were mesmerised as the toy whirred across the room, finally bumping against the ceiling and gently fluttering to the floor. Though the toy soon broke, the image of its flight remained vivid in their minds, prompting them to try and recreate it. This first experience ignited a passion that would shape their lives.

This early interest in mechanical devices was nurtured by their mother, Susan Catherine Koerner Wright, a mechanically gifted woman who often repaired household appliances herself. She instilled curiosity and a hands-on approach to problem-solving in her children.

Wilbur and Orville were largely self-taught, displaying a natural aptitude for technical subjects. Wilbur, a gifted student, originally planned to attend Yale University, but a hockey accident forced him to abandon those aspirations. Orville, more adventurous by nature, channelled his energy into building a printing press while still in high school, demonstrating their shared drive to create and innovate. Together, brothers balanced each other’s strengths.

Want to know how helicopters took flight? Dive into their fascinating history.

The Wright Cycle Company

The Wright brothers pursued several ventures to earn a living. In 1892 they established the Wright Cycle Company. This venture proved successful, expanding from bicycle sales to a repair shop and eventually encompassing the manufacture of their bicycles.

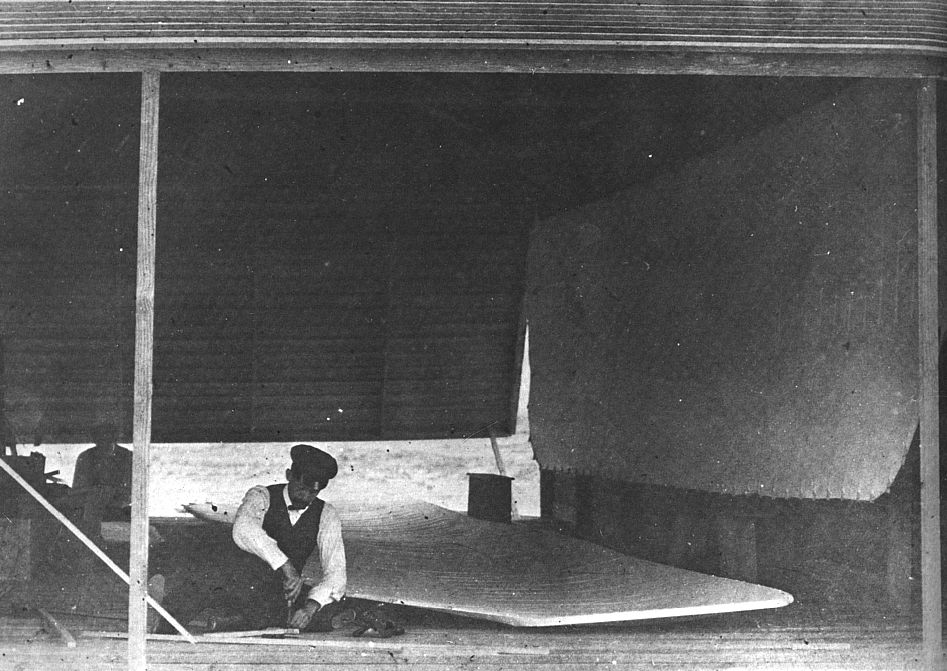

The cycle company served as more than just a financial foundation. It honed their mechanical skills, providing them with valuable experience in precision engineering, problem-solving, and working with intricate mechanisms. Moreover, the shop offered access to a wealth of tools and equipment, many of which would later prove invaluable in their aviation endeavours.

Their renewed interest in flight in 1896 was ignited by two notable events: the tragic death of Otto Lilienthal, a prominent glider pioneer, during a flight test, and the impressive demonstrations of Samuel Langley's unmanned powered models.

Unlike many of their contemporaries who relied on outside funding, the Wright brothers were determined to self-finance their aviation research. Their workshop, nestled within the backroom of their bicycle shop, became their laboratory, a space where they meticulously designed and constructed the components of their groundbreaking aircraft.

Early Experiments in Aviation

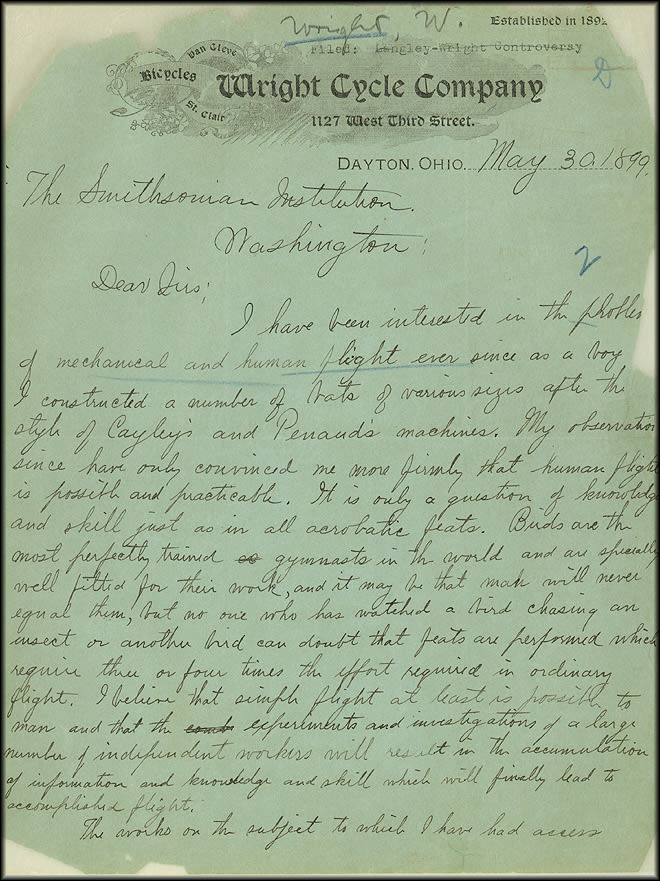

In 1899, Wilbur Wright wrote to the Smithsonian Institution, requesting information on aerodynamics. He and Orville were disheartened by the lack of progress in aviation but felt inspired by the possibility that they could succeed where others had not.

Wilbur initially led their research, with Orville soon joining as an equal partner. They identified that the principles of lift and propulsion were understood but lateral control was the missing element. Rejecting the idea of inherent stability, they believed control should rest in the pilot’s hands.

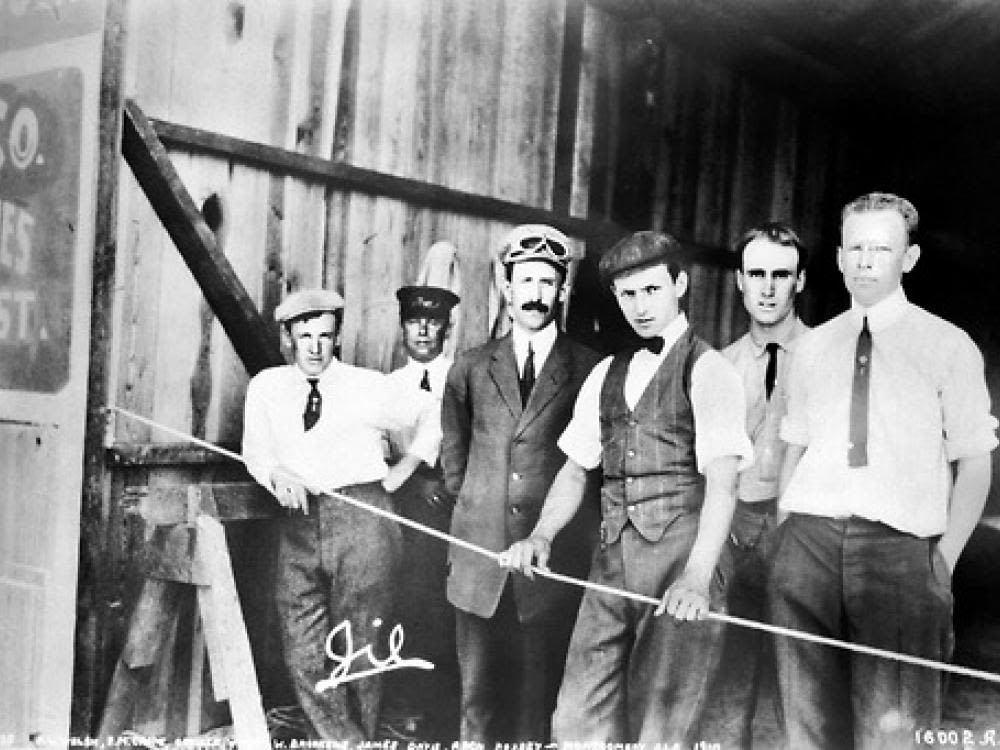

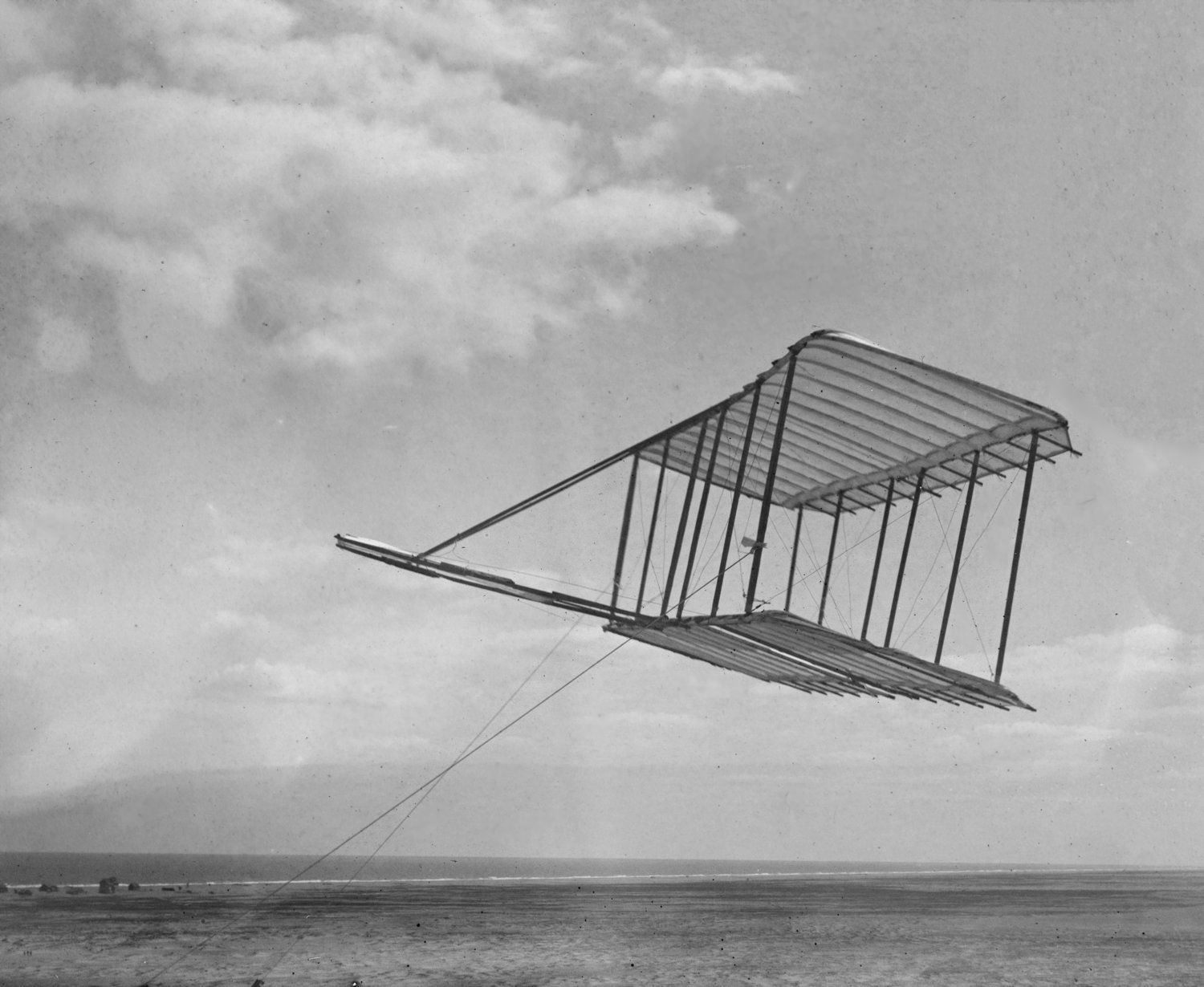

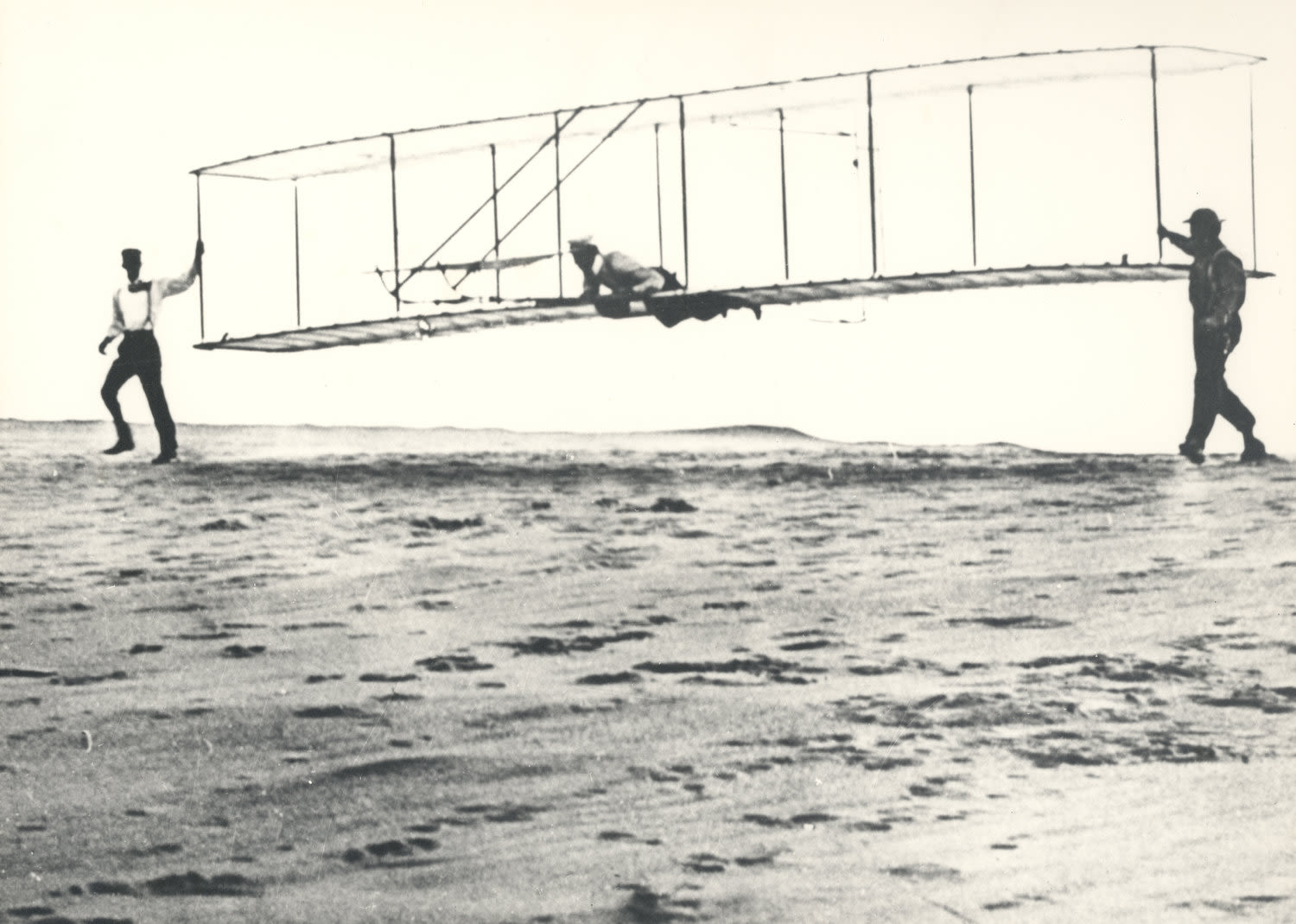

Wilbur conceived the idea of “wing-warping” for lateral control after observing birds in flight and experimenting with a twisted box. Testing this theory with a 5-foot biplane kite, they confirmed it worked. However, Dayton’s weather conditions proved unsuitable for further experiments, so they contacted the National Weather Bureau. They were directed to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, known for its steady winds and soft sand for safe landings. The locals near Kitty Hawk were vital, providing resources, labour, and moral support. The lifesaving station crew helped with logistics and was witness to their achievements.

The First Gliders

1900: The Wrights built a 17-foot glider with a forward lift, which they tested at Kitty Hawk. However, the wings generated less lift than expected, and their free-flight experiments were brief. Discouraged but determined, they returned home convinced they had solved the problem of control but needed to improve the lift.

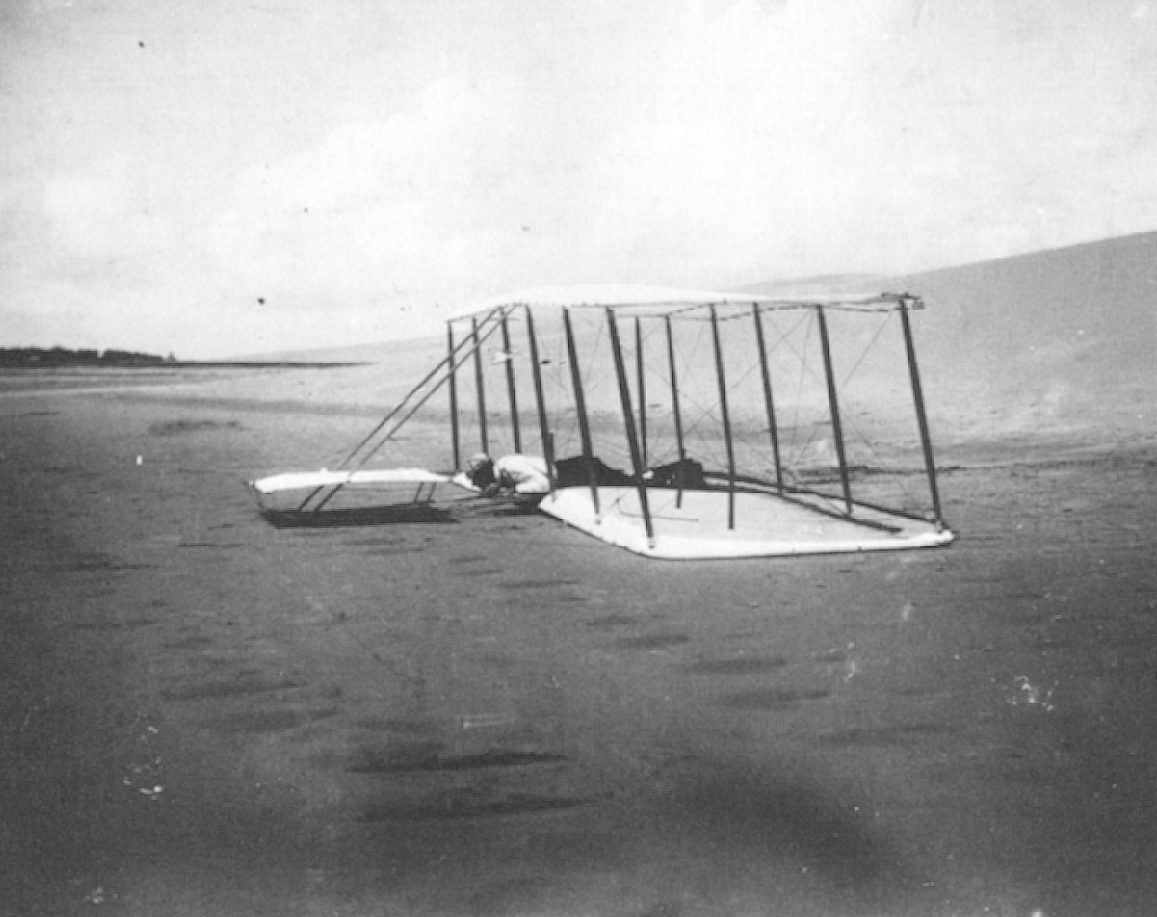

1901: The brothers built a larger glider with a 22-foot wingspan and a more pronounced wing curve (camber). At their new camp in Kill Devil Hills, they faced further setbacks. The glider’s lift was only a third of what they had predicted, and it pitched unpredictably into stalls. Frustrated, they considered quitting but decided instead to build a wind tunnel to gather their data, discovering that much of the earlier aviation research relied on flawed information.

1902: Armed with accurate data, they constructed a 32-foot glider with more efficient wings and vertical tails to counteract adverse yaw. The pilot controlled the machine by moving a hip cradle to warp the wings. Though the glider initially had stability issues, they added a movable tail linked to the wing-warping mechanism, enabling smooth turns. This innovative design marked a turning point. With over 1,000 glides that year, they achieved lateral and longitudinal control, paving the way for powered flight.

The Write Flyer

The brothers now faced the challenge of creating a lightweight engine and efficient propellers. Unable to find a suitable engine on the market, they designed and built their own, producing 12 horsepower. They also developed the first efficient aeroplane propeller, applying data from their wind tunnel.

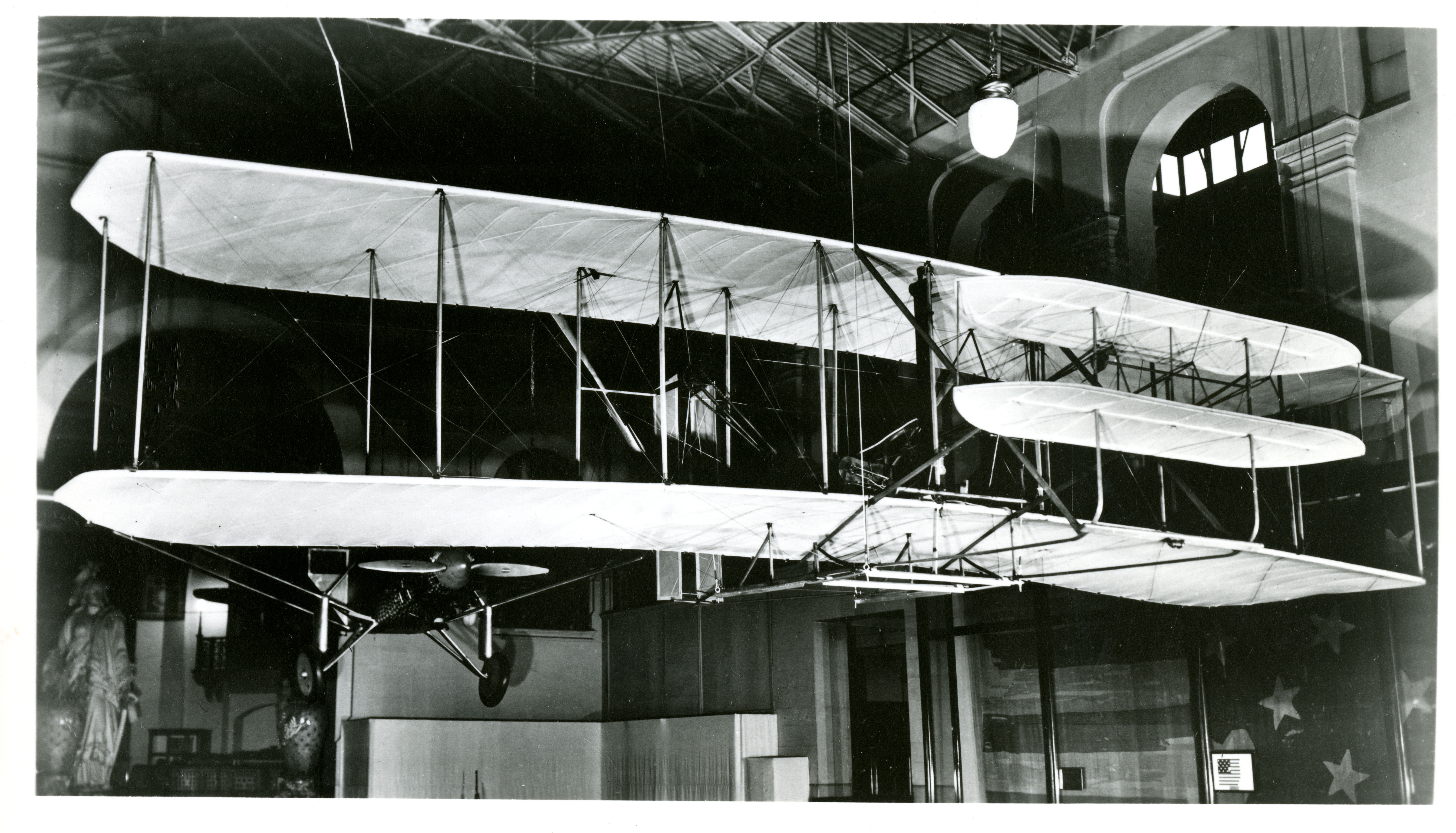

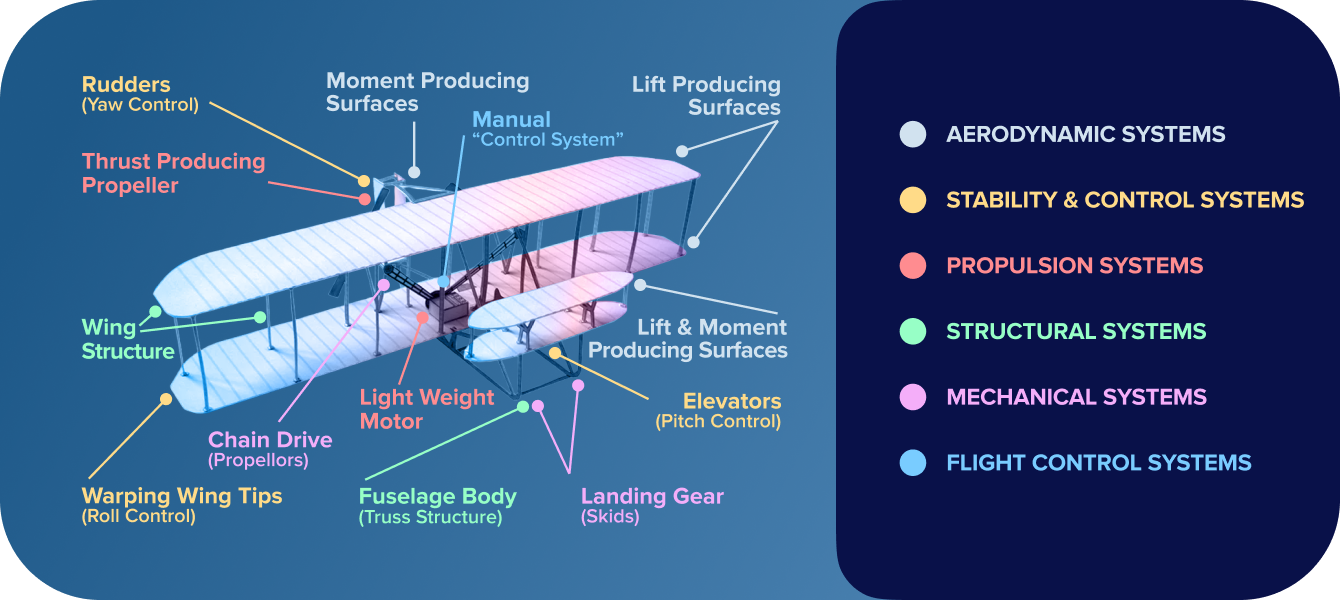

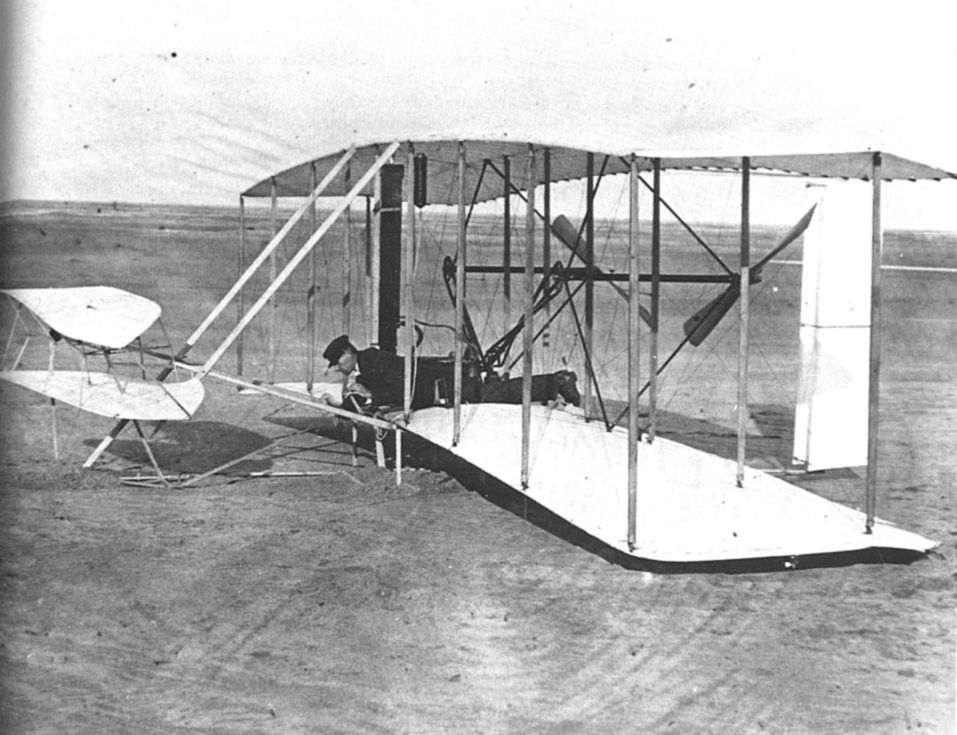

Their final design, the Wright Flyer, had a 40-foot wingspan, weighed 605 pounds, and featured double tails and lifts. The engine powered two pusher propellers, with chains ensuring they rotated in opposite directions to counteract torque. The aerodynamic surfaces were enveloped in a fine muslin fabric, creating a taut and efficient wing.

Powering this innovative machine was a four-cylinder gasoline engine, a product of the Wright brothers' own inventive genius. Developing approximately 12.5 horsepower, the engine drove two counter-rotating propellers via a chain-drive transmission. These propellers spun at an average speed of 348 revolutions per minute, propelling the Flyer forward.

The pilot lay on the lower wing within a padded cradle and controlled the aircraft through a unique system. To steer, the pilot shifted their hips, activating the "wing-warping" mechanism. This ingenious system altered the angle of attack of the wings on each side, effectively raising or lowering the wing tips to achieve roll control and execute turns. A small hand lever controlled the forward lift, providing pitch control and augmenting lift. The rear rudder was ingeniously linked to the wing-warping system to counteract the yawing forces induced by wing-warping.

Recognising the challenges of launching from the soft, sandy terrain of Kill Devil Hills, the Wright brothers devised a novel launch system. They constructed a 60-foot-long monorail track using four 15-foot beams, reinforced with metal strips to ensure smooth travel. The Flyer, supported on two modified bicycle wheel hubs, would accelerate down this track.

At the outset of each flight, the Flyer was secured at the head of the track by a restraining line. The engine, lacking a throttle, could only be started or stopped by controlling the fuel flow. To initiate the flight, the pilot released the restraining line, allowing the Flyer to accelerate down the track and take to the air.

Engineering Breakthroughs

Propeller Design: The Wright brothers’ propellers were groundbreaking because they treated them as airfoils rather than just spinning blades. Their detailed mathematical calculations made them more efficient than any designed before.

Three-Axis Control: Emphasise their pioneering system of controlling an aircraft along three axes (roll, pitch, and yaw). This was one of their most significant contributions to aviation.

Lightweight Engine: Their homemade engine, developed with their mechanic Charlie Taylor, weighed only 179 pounds—light enough for flight, yet powerful enough to work effectively.

Wright Flyer

Wingspan: 40 feet 4 inches (12.29 meters)

Length: 21 feet 1 inch (6.43 meters)

Height: 9 feet 4 inches (2.83 meters)

Wing Area: 510 square feet (47 square meters)

Empty Weight: 605 pounds (274 kilograms)

Engine: 12-horsepower (9 kW) four-cylinder, water-cooled

Propeller: Two counter-rotating propellers, each 8 feet 6 inches (2.59 meters) in length

Maximum Speed: Approximately 30 mph (48 km/h)

The First Powered Flight

The first flight attempt on December 14th met with a setback when Wilbur, at the controls, oversteered, causing the Flyer to stall and crash. Repairs were made, and three days later, they returned to Kill Devil Hills.

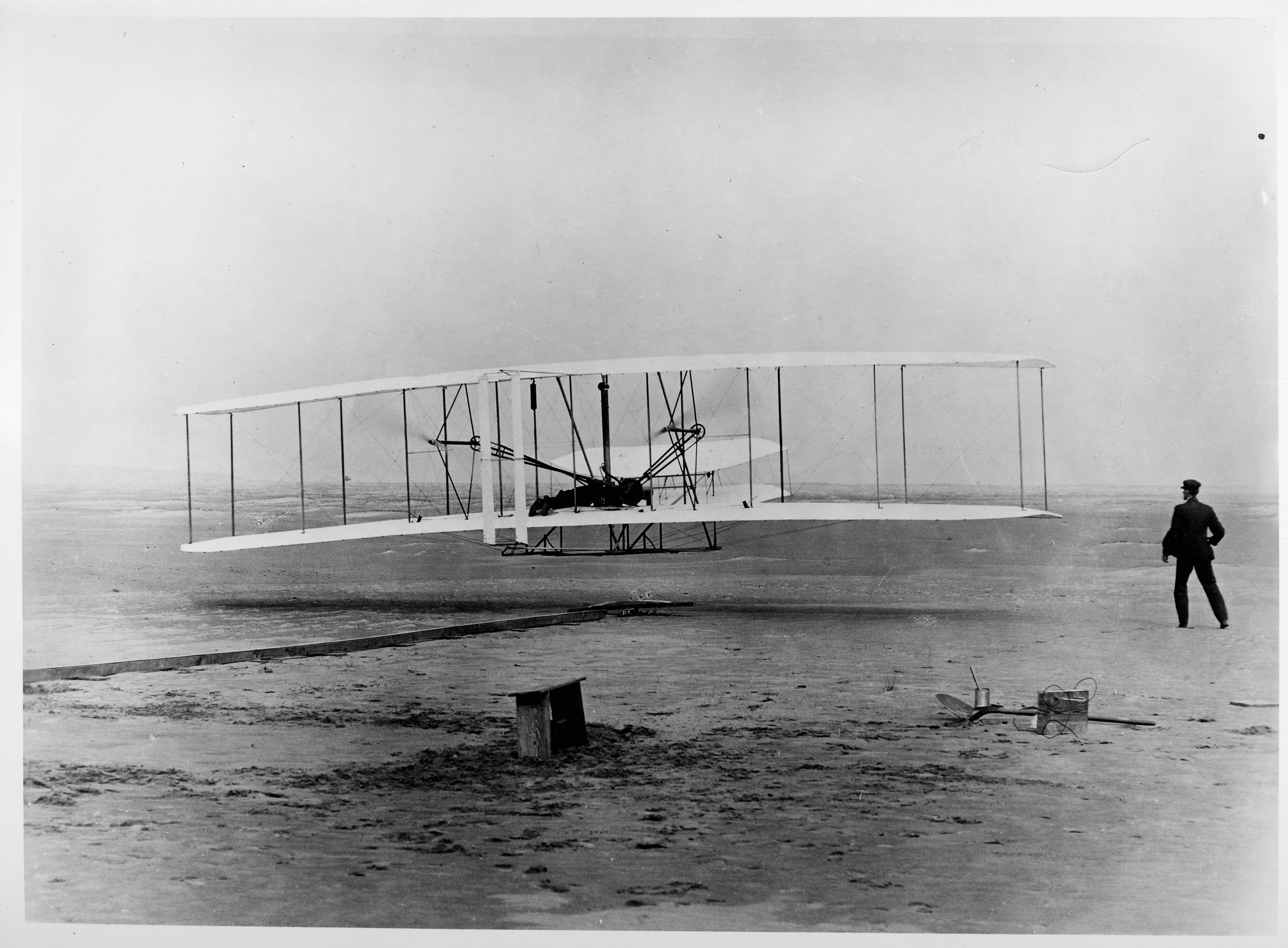

On December 17th, 1903 history was made. Wilbur made the first attempt, but the Flyer stalled after a brief 3.5 seconds in the air. However, later that morning, Orville took control. With a strong headwind aiding their efforts, the Flyer lifted off the launch rail and soared for 12 seconds, covering 120 feet. This historic moment was captured forever by John T. Daniels, a volunteer from the nearby lifesaving station, who photographed the flight using Orville's camera.

The brothers continued their experiments, taking turns piloting the Flyer in three more successful flights. Wilbur achieved the longest flight of the day, covering an impressive 852 feet in 59 seconds. Unfortunately, a strong gust of wind damaged the Flyer after the final flight, bringing their experiments to an abrupt end for the season.

Following their success, the Wright brothers diligently pursued a patent for their flying machine, a process that involved several legal battles and unfortunately delayed wider recognition of their achievement.

In 1908, the Wright brothers took their invention to the world stage. Wilbur demonstrated the Flyer in France, captivating audiences and solidifying their place in aviation history. Orville followed with successful demonstrations in the United States.

Today you can see the original Wright Flyer on display in The Wright Brothers and the Invention of the Aerial Age at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Later Life and Legacy

The Wright brothers’ approach to flight was revolutionary. Unlike others, they understood that piloting skills and control were as crucial as the machine itself. As Wilbur famously said, “It is possible to fly without motors, but not without knowledge and skill.”

Their experiments at Kitty Hawk solved the problem of lift, propulsion, and control, establishing the principles of modern aviation. Within two generations, their work would lead to routine air travel, supersonic flight, and even lunar exploration.

Wilbur died in 1912 from typhoid fever, leaving Orville to carry on their legacy. Orville lived until 1948, witnessing incredible advancements in aviation, including supersonic flight.

The brothers remained humble about their achievements. They viewed themselves as problem-solvers rather than heroes. From using bicycle parts in their planes to developing a wind tunnel, their ability to innovate with limited resources demonstrates their ingenuity.

Their achievement inspired countless dreamers, inventors, and aviators, including Charles Lindbergh, Amelia Earhart, and Neil Armstrong.