Altitude Basics: 5 Types Of Altitude Explained

Altitude is more than just a number on your altimeter — it’s fundamental to safe and efficient flight. But did you know that there are different types of altitude, each serving a unique purpose?

Pilots must interpret altitude correctly from the height above sea level to the aircraft’s position relative to atmospheric pressure to ensure terrain clearance, airspace separation, and aircraft performance.

We’ll break down the key altitude definitions every student pilot needs to know. By understanding these different altitude types, you'll improve your situational awareness, better navigation accuracy, and ultimately become a more confident and safer pilot. Let's get started.

Indicated Altitude (QNH)

What You See on the Altimeter

Indicated altitude is the altitude displayed on your altimeter when it is set to the local pressure setting (QNH). It’s the primary altitude reference pilots use in flight.

It tells you how high you are relative to the standard mean sea level (MSL), assuming the correct local barometric pressure is set. Since pressure changes with weather, incorrect settings can lead to altitude errors.

Pilots must adjust their altimeter to the latest QNH provided by Air Traffic Control (ATC) or airport Automatic Terminal Information Service (ATIS) for accurate readings.

Why It Matters: Indicated altitude is used for terrain clearance, separation from other aircraft, and complying with controlled airspace restrictions.

Beyond the Routine: Understanding Aviation Checklists covers the importance of checklists and how to use them effectively. Discover best practices for checklist management, learn how to avoid common errors, and understand why these procedures are vital for every flight.

True Altitude

Your Actual Height Above Sea Level

True altitude is the aircraft’s actual height above mean sea level (MSL). While it sounds similar to indicated altitude, there’s a key difference: true altitude accounts for variations in temperature and pressure that affect air density.

It’s essential for safe navigation over mountainous terrain, where accurate height above sea level is critical. Approach charts often list minimum safe altitudes (MSA) in true altitude to ensure terrain clearance.

True altitude differs from indicated altitude when standard atmospheric conditions (ISA) don’t exist. Warmer air makes an aircraft fly higher than indicated, while colder air makes it fly lower than indicated — a crucial consideration in high-altitude airports or winter flying.

Why It Matters: Knowing your true altitude ensures terrain clearance and safe descent planning, particularly in IFR operations.

Explore the Standard Atmosphere and its critical elements: air pressure, temperature, and density. Learn how these factors influence lift, aircraft performance, and flight safety. Find out more in ATPL Lessons with Chris Keane: Atmosphere Introduction.

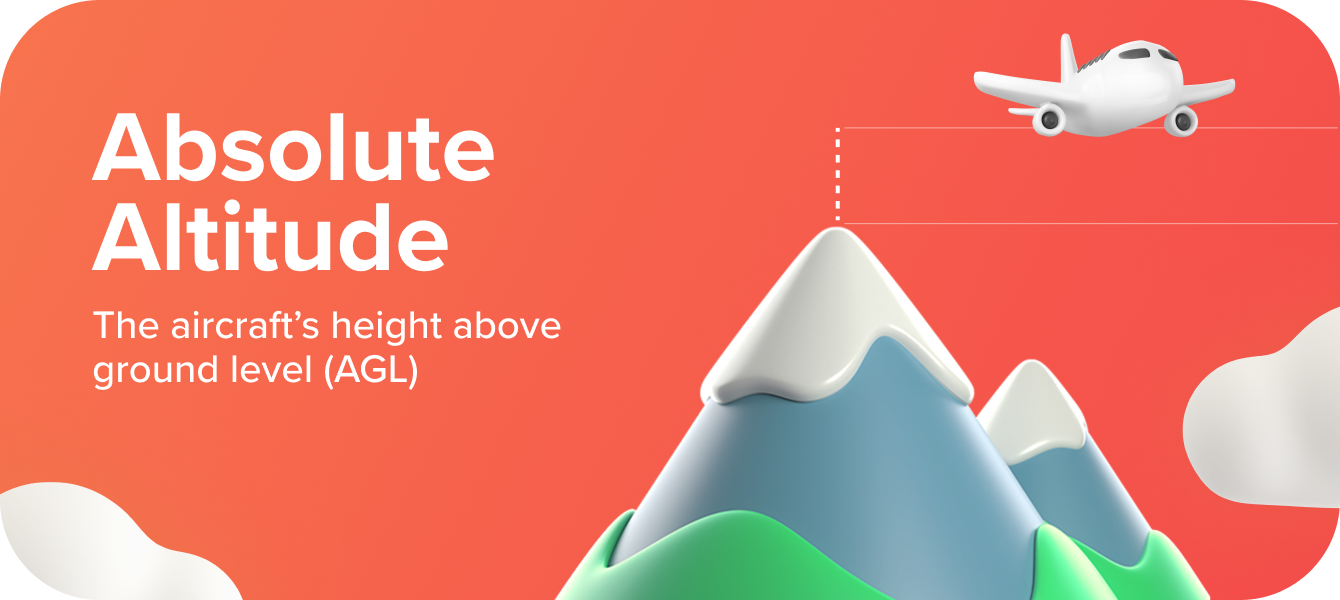

Absolute Altitude

Height Above the Ground

Absolute altitude is your height above the terrain directly beneath you, measured in feet above ground level (AGL).

Absolute altitude changes constantly as terrain elevation changes, unlike indicated or true altitude, which use sea level as a reference. This altitude matters most when flying at low levels, such as during take-off, landing, or obstacle avoidance.

Pilots often rely on radar altimeters (RADALT) or GPS systems to determine their precise absolute altitude, especially in low-visibility conditions.

Why It Matters: Absolute altitude is crucial for safe landings, obstacle clearance, and low-level flight operations like search and rescue or helicopter missions.

Enhance your flight training experience with these 14 essential apps. From flight simulators to real-world weather data, these tools will elevate your learning.

Pressure Altitude

Your Standardised Height in the Atmosphere

Pressure altitude is the altitude your aircraft would be at in the International Standard Atmosphere (ISA), based purely on air pressure. It is the height above the standard pressure level of 1013 hPa (29.92 inHg), regardless of actual weather conditions.

Pilots calculate pressure altitude by setting the altimeter to 1013 hPa and reading the displayed altitude. ATC assigns pressure altitude when transitioning to flight levels (FL), so all aircraft can use the same reference point and avoid conflicts due to local pressure changes.

It is used in performance calculations, as aircraft manufacturers use pressure altitude to determine climb rates, fuel burn, and take-off/landing distances.

Why It Matters: Pressure altitude is vital for high-altitude operations, flight level transitions, and aircraft performance planning, ensuring consistency in altitude separation across global airspace.

Density Altitude

The Altitude That Affects Performance

Density altitude is pressure altitude corrected for temperature and air density variations. It represents how high the aircraft “feels” like it’s flying due to atmospheric conditions.

High temperature, low pressure, and high humidity increase density altitude, making the air thinner, or less dense. This reduces engine power, climb rate, and lift, significantly affecting take-off and landing performance.

Hot and high-altitude airports (like those in Spain, Switzerland, or the Alps) often have dangerously high density altitudes, requiring longer runways and reduced aircraft loads.

Pilots use performance charts to adjust take-off speeds, fuel calculations, and required runway lengths based on density altitude.

Why It Matters: Density altitude is crucial for safety in take-off and landing, particularly in hot, high, and humid conditions where reduced aircraft performance could lead to longer take-off rolls or poor climb rates.

So far, we’ve explored the five primary altitude types —Indicated, True, Absolute, Pressure, and Density Altitude. Now, we move on to two additional altitude references essential for high-altitude operations: Flight Levels and Transition Altitudes/Levels. These standardised altitude measurements help ensure safe vertical separation and seamless coordination in controlled airspace. Let’s have a closer look at how they work.

What is Zulu time, why does it exist, and how can you easily calculate it yourself? Read on to find out more.

Flight Level (FL)

Standardised Altitudes for High-Altitude Operations

A Flight Level (FL) is a standardised altitude reference used in aviation, measured in 100-foot increments above the standard datum plane (1013.25 hPa / 29.92 inHg). Unlike traditional altitude, which is based on local air pressure (QNH), flight levels provide a consistent altitude reference across all airspace, reducing errors caused by changing atmospheric conditions.

Instead of referring to mean sea level (MSL), flight levels are referenced to a fixed pressure level. For example:

FL100 = 10,000 feet (above the standard pressure plane)

FL250 = 25,000 feet

FL350 = 35,000 feet

The use of flight levels typically starts at 18,000 feet in some regions (such as North America), but in Europe and the UK, the FL is lower, often between 3,000 and 6,000 feet, depending on the country. Above this point, pilots switch to standard pressure settings and fly using flight levels instead of indicated altitude.

Why It Matters: At high altitudes, atmospheric pressure fluctuates significantly due to weather changes. If pilots used local QNH settings, aircraft at the "same altitude" could be flying at different actual heights, increasing collision risk. Flight levels eliminate altitude discrepancies caused by local pressure variations, improving separation, communication, and air traffic control efficiency in high-altitude operations.

Discover how to enhance your flight training experience and build a strong relationship with your instructor in our article Pilot in the Making: Mastering Flight Training.

Transition Altitude & Transition Level

Switching Between Local and Standard Pressure

As pilots climb or descend, they must transition between using local QNH (for indicated altitude) and standard pressure settings (for flight levels). The points where this switch happens are called the Transition Altitude (TA) and Transition Level (TL).

Transition Altitude (TA): The altitude at which an aircraft switches from local barometric pressure (QNH) to the standard setting (1013.25 hPa).

Transition altitudes differ significantly across regions. In the US and Canada, it's a fixed 18,000 feet (5,500 meters), while in Europe, it varies, sometimes as low as 3,000 feet (900 meters). Within the Eurocontrol area, efforts are underway to standardise this altitude. Specifically, in the UK, transition altitudes range between 3,000 and 6,000 feet, depending on the airport. Below this, pilots fly using indicated altitude based on local pressure.

Transition Level (TL): The flight level at which an aircraft switches from standard pressure back to local QNH when descending.

The transition level varies based on atmospheric pressure and is usually between FL50 and FL70. ATC provides the current transition level for arriving aircraft.

Example: A pilot departing London Heathrow (EGLL) climbs using local QNH until reaching the transition altitude (e.g., 5,000 feet). At this point, they switch the altimeter to 1013 hPa and start using flight levels (e.g., FL60, FL100). Upon descent, ATC will inform the pilot of the transition level (e.g., FL60), where they must reset their altimeter back to local QNH.

Why It Matters: Transition altitudes and levels ensure smooth altitude changes, prevent confusion between local and standard pressure settings, and maintain safe separation between aircraft in different flight phases.

Airhead's Takeaway

Altitude management in aviation depends on clear and consistent standards. Whether using indicated altitude, and flight levels, or transitioning between them, pilots must stay aware of pressure settings to ensure safety, efficiency, and compliance with ATC instructions.

Throughout this guide, we’ve covered:

Indicated Altitude – What you see on the altimeter when set to local pressure (QNH).

True Altitude – Your actual height above mean sea level (MSL), is crucial for terrain clearance.

Absolute Altitude – Your height above ground level (AGL), is essential for takeoff, landing, and obstacle awareness.

Pressure Altitude – The altitude based on standard pressure (1013 hPa), used for performance calculations and transitioning to flight levels.

Density Altitude – Pressure altitude corrected for temperature, impacting aircraft performance, especially in hot and high conditions.

Flight Levels (FL) – Standardised altitude references above the transition level, ensuring safe airspace separation at high altitudes.

Transition Altitude & Transition Level – The points where pilots switch between local QNH and standard pressure settings.