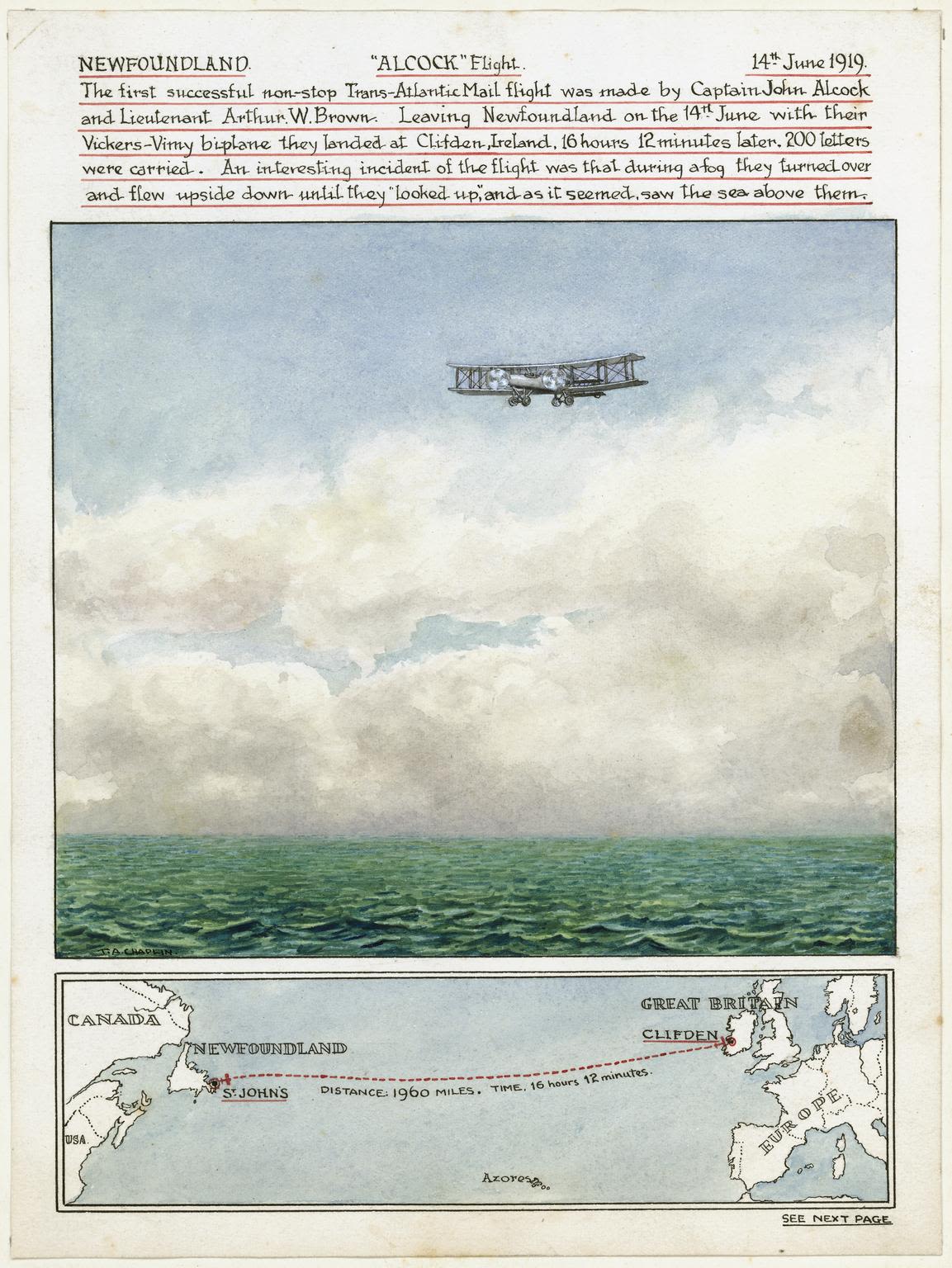

Pioneers of the Skies: The First Non-Stop Transatlantic Flight

In the earliest days of aviation history, few moments are as significant as the first non-stop transatlantic flight accomplished by Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten-Brown.

On June 14, 1919, the duo took off from Lester's Field near St. John's, Newfoundland, and after 16 hours and 27 minutes, they landed at Clifden, Ireland. Their journey was not just a milestone in aviation but a testament to human endurance, innovation, and bravery.

Their daring feat captured global attention, and upon their arrival in London, they were celebrated as heroes. Winston Churchill, then Britain's Secretary of State, awarded them Lord Northcliffe's Daily Mail prize of £10,000. A few days later, they were knighted by King George V at Buckingham Palace.

Let's delve deeper into the fascinating details of Alcock and Brown's pioneering flight, the preparations leading up to it, and the broader context of early aviation.

The Background and Preparations

The ambition to cross the Atlantic by air had been brewing for several years. During World War I, the technological advancements in aviation had accelerated rapidly. Aircraft were becoming more reliable, with improved engines, navigation systems, and aerodynamics. This progress fuelled the desire to push the boundaries of what was possible in peacetime.

John Alcock and Arthur Whitten-Brown were both experienced aviators. Alcock had been a Royal Naval Air Service pilot during the war, known for his flying skills and determination. Brown, an officer in the Royal Flying Corps, brought a wealth of navigation expertise. Together, they formed a perfect team to tackle the daunting challenge of a transatlantic flight.

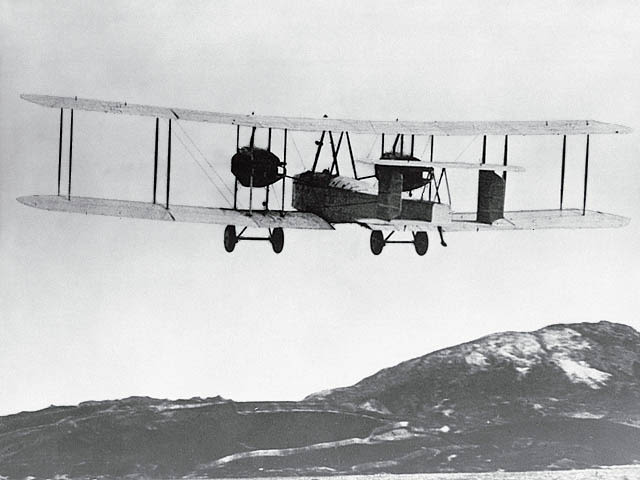

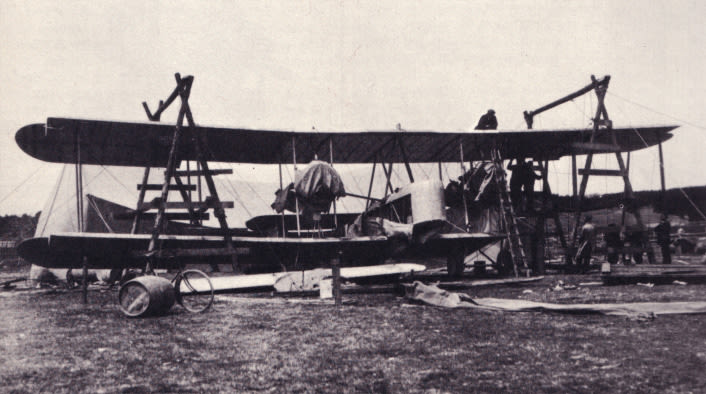

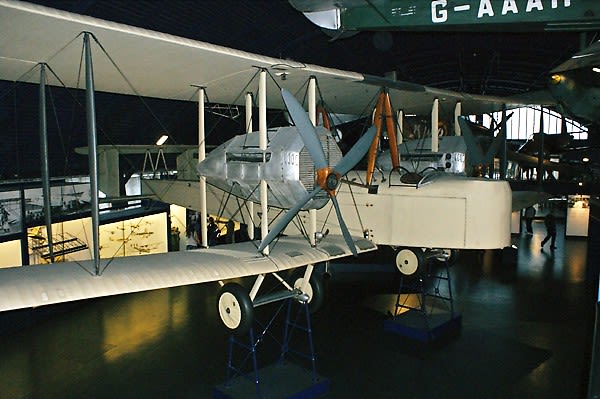

Their aircraft, the Vickers Vimy IV, was a modified World War I bomber. It was chosen for its long-range capabilities and robust construction. The modifications included extra fuel tanks to extend its range and reinforced structures to handle the rigours of a long flight over open water. The Rolls-Royce Eagle engines, renowned for their reliability, powered the Vimy.

The preparations for the flight were long and complex. Over three weeks, Alcock and Brown, along with their team, worked tirelessly to ready the aircraft and plan their route. They faced numerous challenges, including finding a suitable take-off point. The rough terrain around Lester's Field was far from ideal, but after a week of searching for better options, they decided to proceed from there.

On the day of departure, the weather was overcast, contrary to the meteorological report's forecast of favourable conditions. Despite this, Alcock and Brown were determined to proceed.

At 1:40 p.m., with engines roaring at full power, they taxied over the bumpy ground and lifted off at 1:45 p.m., narrowly clearing the trees at the airfield's edge.

The Challenges of the Atlantic Crossing

1,890 nautical miles of open sea lay ahead. The first four hours of their journey were peaceful, but soon, fog banks appeared on the horizon. "We've got no choice," Alcock said. "We've got to go in!" As the Vimy disappeared into the fog, the two men could no longer see the propellers. The comforting roar of the Rolls-Royce "Eagle" engines was silenced, and they flew virtually soundless and blind.

The fog was thick, and time passed slowly. At 6 p.m., they encountered a terrifying noise: the right-hand engine sounded like a machine gun blazing. The exhaust pipe had split, and the engine was shooting naked flames. Adding to their discomfort, the heating in their leather flying suits stopped working. They were now flying in freezing conditions, blind, and with a malfunctioning engine.

Battling the Elements

Flying above the fog brought no respite as clouds loomed above them. The Vimy plunged into the clouds, tossed around like a leaf, and both men felt severe physical discomfort. Alcock regained control of the Vimy at a mere 65 ft. above the waves, an altitude dangerously close to the sea. They ascended to 7,200 ft. but were still chilled and deafened by the noise of the right-hand engine.

Their frugal meal of sandwiches, prepared by Miss Agnes Dooley at St. John's, was a welcome break. They also had whisky and beer, which they emptied and threw overboard. Regular checks were made on the engines, cooling system, oil pressure, and fuel consumption. Brown was thankful for the task as it kept him warm.

Navigation and Endurance

After five hours of flying, they saw the sun, and Brown calculated their position. They were a few miles south of their planned route. Soon after, they were swallowed by clouds again, flying blind until 9 p.m. Midnight came, and they were still surrounded by clouds and darkness. At 12:15 a.m., Alcock pointed above his head. There was the moon, Vega, and the Pole Star, Polaris. Brown quickly calculated their position: 50 deg 7' latitude north, 31 deg longitude west. They had flown 850 nautical miles, with 1,000 more to go.

Their spirits lifted, and they enjoyed more sandwiches and coffee laced with whisky. Brown sang, but Alcock could not understand a word.

Meanwhile, there was concern in London's "Daily Mail" newsroom. The Vimy had yet to be heard from since its takeoff. The newspaper staff knew the plane carried a radio transmitter, but it had gone dead after three hours of flight.

A Descent into Danger

At 3:00 a.m., the fliers encountered another mountain of cumulus cloud. They were flung out of control, drenched by rain that turned into hail, and the airspeed indicator jammed. Alcock struggled to regain control, managing to level the Vimy just above the sea. Brown thought of Lieutenant Clement's weather report, which had failed to forecast the snowstorm they now faced.

Snow covered the plane, and ice formed on the engines. Brown knew he had to clear the ice from the air filters. Braving the slipstream and frost, he climbed onto the wings, removing ice from the inspection windows and the inlet connections. Alcock kept the plane steady at 8,000 ft. Brown repeated the dangerous task four times.

The Final Stretch

At 6:20 a.m., the controls were not operating due to icing. At 11,800 ft., the sun appeared, and Brown calculated their position. They were still on course but needed to descend to prevent the controls from freezing. At 1,000 ft. above the ocean, the ice began to melt. They were soon sitting in a puddle, and the engines ran smoothly again.

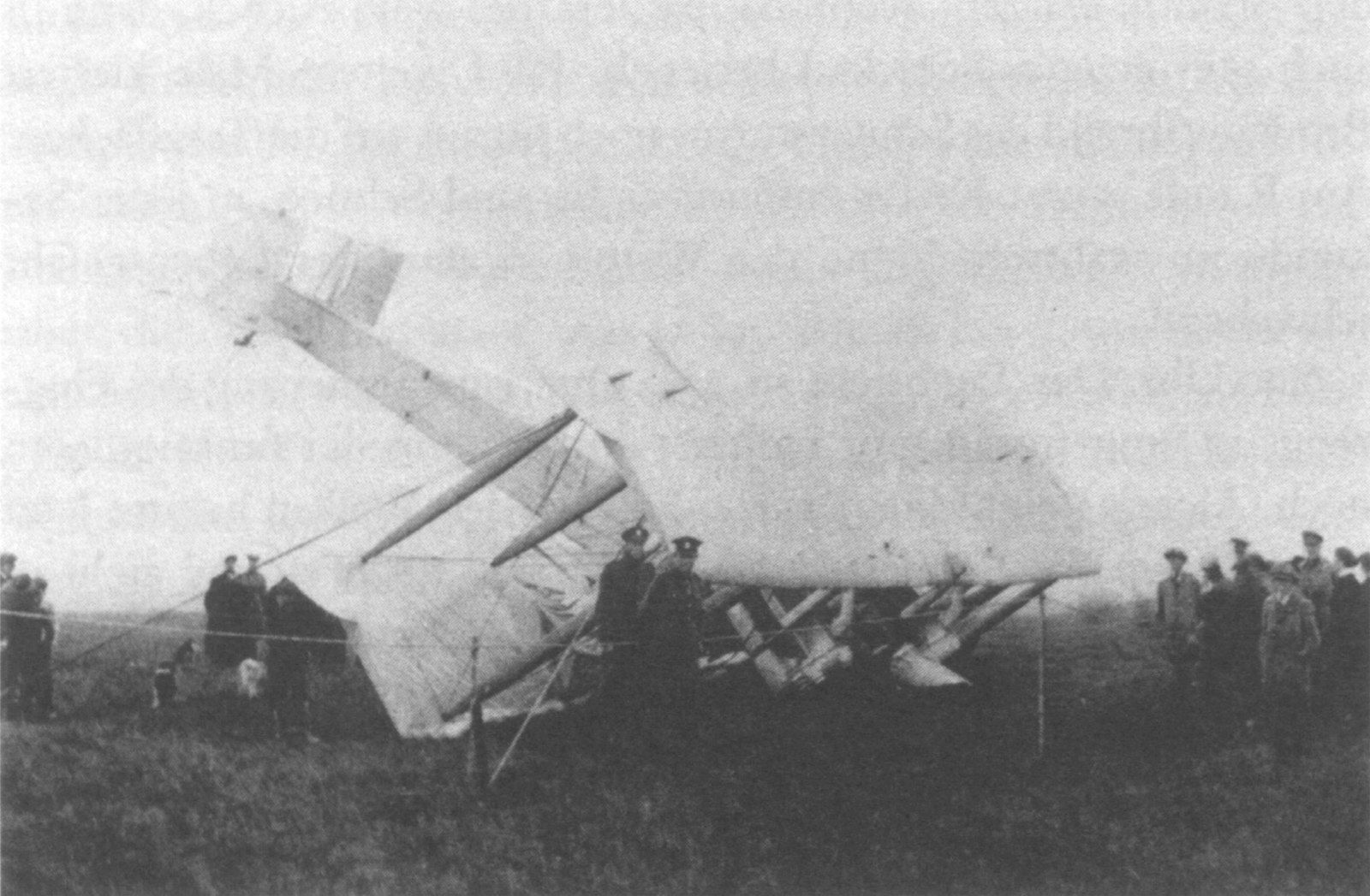

Twenty minutes later, they sighted land. It was not Galway, but Brown identified it as Ireland. They headed toward Clifden, circled over the town, and looked for a landing spot. Alcock brought the Vimy down into Derrygimla Moor, a swampy area.

After 1,890 miles and 16 hours and 27 minutes, they had landed. They were greeted by a man named Taylor, who asked, "Anybody hurt?" "No." "Where are you from?" "America."

Heroes' Welcome

News of their adventure spread like wildfire. Alcock and Brown were celebrated as heroes, greeted with receptions, speeches, galas, and banquets. In Clifford Street, London, Brown made his shortest speech: "No speech now. You wanted us. Here we are!"

At a banquet, they enjoyed a special menu: Oeufs Poches Alcock, Supreme de Sole a la Brown, Poulet de Printemps a la Vickers Vimy, Salade Clifden, Surprise Britannia, Gateau Grand Success.

Winston Churchill awarded them Lord Northcliffe's £10,000 prize, which they shared with the Vickers and Rolls-Royce mechanics. A few days later, they were knighted by King George V at Buckingham Palace, becoming Sir John Alcock and Sir Arthur Whitten-Brown.

The Broader Context of Early Aviation

The early 20th century was a period of rapid advancements in flight technology. The Wright brothers had made their first powered flight only 15 years earlier, in 1903. Since then, aviation has developed at an astonishing pace, largely driven by the demands of World War I.

During the war, aircraft had been used for reconnaissance, combat, and strategic bombing. This period saw significant improvements in aircraft design, engine performance, and pilot training. However, long-distance flights over open water remained a major challenge due to the limitations of navigation technology and the reliability of engines.

The idea of a transatlantic flight had been circulating among aviation pioneers for several years. In 1913, the Daily Mail had offered a £10,000 prize for the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic, but World War I delayed any serious attempts. After the war, with advancements in aircraft technology and a surplus of skilled pilots, the race to claim the prize resumed.

Technological Innovations and Their Impact

The Vickers Vimy IV, used by Alcock and Brown, was a testament to the technological innovations of the time. Originally designed as a bomber, it had a robust construction and the ability to carry significant payloads over long distances. The modifications made for the transatlantic flight included additional fuel tanks to extend its range, which was crucial for the 1,890-mile journey.

The Rolls-Royce Eagle engines were another critical component. Known for their reliability, these engines provided the necessary power and endurance.

However, the flight also highlighted the limitations and challenges of the technology. The split exhaust pipe, the heating failure in the suits, and the icing on the engines and controls were all reminders of the era's technological constraints.

Navigation was another significant challenge. Pilots relied on basic instruments, dead reckoning, and celestial navigation in an era before GPS. Brown's skill with the sextant and his ability to calculate their position under difficult conditions were crucial to their success. This aspect of their flight underscored the importance of navigational expertise in early aviation.

Legacy and Inspiration

As we mark the 105th anniversary of this milestone, we celebrate not just the achievement but the courage and determination of two men who dared to dream and made history. Their legacy lives on, inspiring new generations to push the boundaries of aviation and explore the endless possibilities of flight.

Their flight proved that long-distance air travel was feasible, paving the way for the development of commercial aviation. The technology and techniques developed for their flight led to several technological advances in aircraft design and navigation.

Moreover, their achievement was a significant milestone in the cultural perception of aviation. It captured the public's imagination and demonstrated the potential for air travel to connect distant parts of the world.

As we look to the future of aviation, their story continues to inspire and remind us of the incredible progress that can be achieved through constant effort and innovation. Alcock and Brown's non-stop transatlantic journey, fraught with peril and challenges, remains a testament to human ingenuity and bravery.

Photo Credits wikimedia.org, aviation-history.com